I’m not a fan of US foreign policy. I think it’s far too imperialistic, and it seems to me that military interventions abroad rarely achieve their aim and usually cause mass suffering and provoke cycles of violence. I also think that US actions in the past have helped shaped Iran, Russia, and China into the countries that they are today.

Whenever someone brings up Putin’s illegal and immoral annexation of Crimea in 2014, I’ll be sure to mention NATO’s illegal and immoral1 bombardment of Serbia fifteen years prior. When someone complains about China’s “unfair trading practices,” I’ll note that the US has been trying as hard as possible to stunt China’s economic development for the last decade (a policy I’m opposed to). When people bemoan Iran’s hatred of America and the West, I’ll argue that Iran has good reason to hate and fear America, considering that America backed Saddam Hussein in his brutal war with Iran and that prominent hawks in the US are constantly raring for war with Tehran.2

But most keen readers will notice that it seems I’m appealing to the whataboutism logical fallacy, where one defends the condemnable actions of Russia, China, and Iran by noting that America has done bad things in the past, too. But my intent is not to justify immoral actions taken by foreign leaders. Of course it doesn’t justify Putin’s war on Ukraine to point out that America conducted a similarly brutal and illegal war on Iraq twenty years ago. Both wars are immoral and condemnable. Rather, I want to point out that by recognizing its own faults and crimes, America can learn a lot about the motivations and intentions of its adversaries, which helps it craft better policy.

From the fall of the Soviet Union until now, America has pursued global geopolitical primacy, ignoring international law and the security interests of others states and intervening militarily wherever it pleased.3 Such a hubristic foreign policy inevitably involved many transgressions, which were viewed as aggressive by other states. Other powers quite reasonably fear America, given how aggressive and erratic America has been, invading countries left and right, toppling regimes it doesn’t like, and supporting revolutions in countries allied with its adversaries.

These provocations help explain why other countries feel threatened by America and take actions contrary to America’s wishes. Much of those actions, while perceived as aggressive in Washington, are meant to defensively hedge against America. An impartial review of the recent history of geopolitics suggests that we ought to attribute malfeasance by Russia, China, and Iran less to some kind of inherent anti-American belligerence and more to geopolitical circumstance. (Of course, this insight is non-normative and does not imply any particular moral beliefs about what actions should be praised and condemned. I still feel quite comfortably condemning bad things that Russia, China, and Iran do.)

Westerners generally accept that America is not motivated by a fundamentally malign nature but rather acts due to a mixture of geopolitical circumstance and ideology.4 By pointing out the similarities between the US’s past foreign interventions and aggressive actions taken by Russia, China, and Iran, I hope to convince you that it’s very reasonable to see said actions as being motivated, at least in large part, by circumstance as well. If you’re able to regard America’s invasion of Iraq, bombardment of Yemen and countless other countries, and recent efforts to overthrow democratic leaders as being motivated not by pure evil but as awful and stupid mistakes based on the anxieties of a great power (as I do), surely you can extend that same grace to other great powers.

As Van Jackson and Michael Brenes argue, America needs to embrace “security dilemma sensibility,” or “the ability to understand the role that fear might play in [other countries’] attitudes and behaviour, including, crucially, the role that [America’s] actions may play in provoking that fear.” Without whataboutism—i.e., a recognition of America’s past transgressions—it’s very difficult to cultivate that security dilemma sensibility.

The security dilemma in international relations comes about because countries cannot know one another’s intentions. Thus, an aggressive military action taken by one country that is defensive in intent can be interpreted as offensive by other powers and vice versa. Whether we should attribute aggression to inherent belligerence or to circumstance is difficult to determine, and attribution error prevents us from doing this rationally and impartially. This is because we like to think that we always have the best, most moral of intentions whereas our opponents are evil or obsessed with some kind of insane messianic mission.

The issue of what motivates the West’s foes is of vital importance. When we assume that they’re motivated purely by irrational hatred of us, the only sensible policy is one of maximum pressure and confrontation. But when we realize that our opponents can be reasoned with, peace and cooperation become possible. And international peace and cooperation are essential for addressing the greatest threats to humanity: risk from nuclear and biological weapons, AI, pandemics, and climate change.

Why do they hate us?

If you’re at all familiar with American foreign policy discourse, you’ll be aware of this rhetorical strategy used to justify the policy of hawkism and primacy: there’s an axis of conniving, evil actors out there who are set on destroying the West. Our enemies hate us not for what we do but for who we are.

Chief foreign affairs correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, Yaroslav Trofimov, perfectly expressed this view:

Today, Russia and China are revisionist powers dreaming of past imperial glories, seeking to build or restore their spheres of influence and redress what they perceive as historical injustices, such as the loss of Ukraine or Taiwan. To this axis, and to its lesser clients from Venezuela to Belarus, the so-called “rules-based international order” is merely a tool to disguise American domination.5 They believe that rolling back Western political and economic influence, and Western-promoted norms such as liberal democracy, is only natural given the shrinking share of Western democracies in the global economy and population.

Trofimov attributes Russian and Chinese aggression to deep-seated imperial ideologies. These countries are fixated on checking the West and expanding through military conquest. He frames geopolitics as a game of Good versus Evil, in which the rules-based-order is under attack by a confederacy of nefarious villains.

This attitude exemplifies fundamental attribution error, the final boss of terrible foreign policy. It’s when we attribute foreign adversaries’ wrongdoings to their supposed fundamental ideology (while attributing America’s own transgressions to circumstance). If it really were the case that America supported the rules-based international order, then maybe Trofimov would have a point. Maybe it would be reasonable to assume that Russia and China are motivated by pure depravity and hatred of the West. Maybe we would be living in a Democracy-Versus-Autocracy world. But this is not the case. The foreign policies of China, Russia, and Iran aren’t that mysterious or incomprehensible. And America does not support the rules-based international order.

America does not support the rules-based international order.

The cornerstone of international law is state sovereignty and the prohibition against trans-border aggression. You cannot go around attacking other countries unless the UN Security Council says it’s OK or you’re acting in self-defence. America has continually ignored this, conducting many illegal military invasions and interventions since the fall of the Berlin Wall:

Panama (1989)

Yugoslavia (1999)

Libya (2011, where the scope of action clearly exceeded the UNSC mandate)

Pakistan (2004-2018)

These were/are all illegal, much in the same way that Russia’s invasion of Ukriane is illegal. Though people in the West will often try to find justifications for these interventions (promoting democracy, preventing massacres, overthrowing dictators, fighting terrorism), their illegality remains clear in international law. (And their efficacy at achieving their supposed aims is highly dubious.) The whole point of having laws is to make sure everyone abides by the sames rules, even if they feel like they shouldn’t have to.

America does not value human rights or democracy very much:

America's post-9/11 wars resulted in millions of civilian casualties.

America operates the Guantanamo Bay detention camp where prisoners are held indefinitely without trial.

America tortured people at CIA black sites worldwide.

America provides military aid to authoritarian regimes with awful human rights records and floods conflict zones with weapons.

America funded Israel’s war in Gaza, about which AirWars wrote: “By almost every metric, the harm to civilians from the first month of the Israeli campaign in Gaza is incomparable with any 21st century air campaign. It is by far the most intense, destructive, and fatal conflict for civilians that Airwars has ever documented.”

America supports many repressive, illiberal regimes, such as Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Morocco, Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Azerbaijan.

America refuses to join the International Criminal Court and has threatened ICC officials.

America conducts mass surveillance of its citizens.

Other countries have plenty to be genuinely upset about and fearful of.

We should expect other powers to attempt to build up their militaries, consolidate regional power, expand their spheres of influence, manipulate weaker countries to their advantage, and establish political and economic blocs in opposition to the West. This is what self-interested, rational states do in geopolitical environments such as the one that America cultivated. They see this as the best strategy for maintaining their own security because they cannot rely on international law. It’s not necessary to presume that other countries are motivated by irrationally aggresive imperial ideologies.

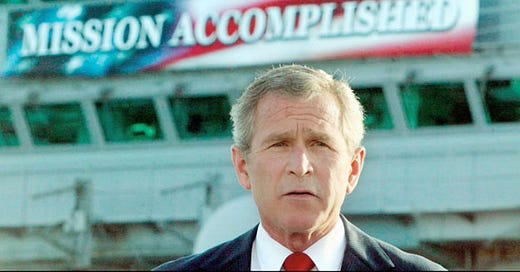

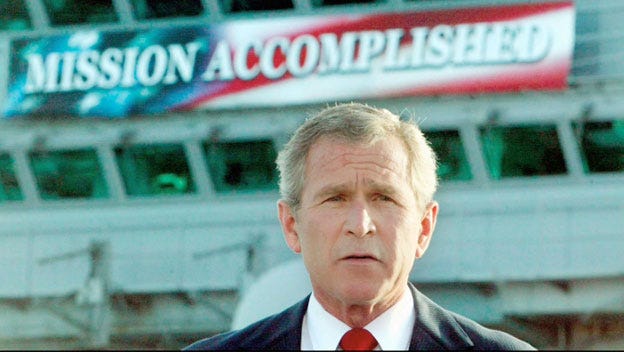

Remember when the pundits, media, and think tankers last rolled out the “Axis of Evil” argument? Is was when George W. Bush was in power. He proclaimed that Iran, Iraq, and North Korea were working together to sponsor terrorist attacks against America and that they were implacably evil: they’re not motivated by reason but by some kind of primordial wickedness.

Of course this is not true. There were reasons that the Axis of Evil countries didn’t like America—reasons can be good and bad and just and unjust, but they exist nonetheless! And there was no evidence that these countries were working together (Iran and Iraq were basically arch nemeses).

Though the Axis of Evil narrative is basically false, it can self-fulfilling.

puts it thus: “To the extent that [China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea] are working more closely than they have in the past, aggressive U.S. policies have encouraged that collaboration. The U.S. pursuit of dominance in every region creates incentives for regional powers to assist each other.” As I’ve pointed out before, Western efforts to economically punish, diplomatically isolate, and politically delegitimate other large powers pushes them to work together in predictable ways. However, they extent to which they work together tends to be overblown in mainstream discourse.Democrats and Republicans alike have adopted the Axis of Evil worldview. Democratic congressman Adam Smith of Washington labels America’s greatest threats6 with the piquant yet youth-friendly acronym CRINGE (China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and Global Extremists)—a.k.a. the Axis of Upheaval. Smith says that this diverse array of actors is making a “coordinated effort” to take on America and “smash” its supposedly liberal world order.

Let me assure you: Iran’s proxies not coordinating with Beijing to annihilate America.7 This is preposterous. Each of these actors has their own particular beef with the West. They work together when their interests converge, and they don’t when their interests are at odds. For example, China buys Iranian oil. Is this proof that Beijing seeks to back Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis and cause mayhem in the region? Probably not. In fact, China has pressed Tehran to rein in the Houthis. If anything, China’s Mideast policy is focused on maintaining stability—Beijing notably brokered a Tehran-Riyadh rapprochement in early 2023. The most reasonable explanation for why China buys Iranian oil is because it’s cheap (thanks to US sanctions).

Regarding China and Russia, this recent Brookings report writes that “[w]hile China and Russia’s partnership runs deep … the ‘axis’ narrative suggests greater solidarity among this grouping than is merited. This clouds strategic analysis and policy creativity, and it enhances the propaganda value of the grouping to the detriment of U.S. interests.”

Any suggestion that CRINGE is working together out of pure, irrational hatred of freedom and liberal values obfuscates the historical developments that led to strife between the West and these actors. It’s bad to ignore said historical developments because it prevents us from addressing the underlying causes of conflict between these countries and the West.

The issue with viewing the world through the Manichaean Axis of Evil lens is that it implies awful foreign policy prescriptions. If our enemies really are motivated purely by an irrational hatred of us, they cannot be reasoned with. There’s nothing we can do but try to eliminate them. Time and time again, by buying into this false narrative, America has pursued a whac-a-mole foreign policy in which the solution for dealing with perceived threats is always the same: bomb the bejesus out of them. This tends to have unintended and harmful consequences.

And the assertion that America’s adversaries are all motivated by evil and working together suggests that our war on evil ought to be fought on many fronts: we can’t eliminate evil just by defeating Russia; we must also take on Iran, China, and every other member of the conspiracy against America.

The Czech Foreign Minister, Jan Lipavský, expressed this mistaken and dangerous sentiment: “The violence happening right now in the world proves one thing: We don’t have anymore the conflicts that are separated from each other and that could be handled separately. There is one common effort to destroy the international order, and we have to do everything to prevent that.”

The truth is far more complicated than that.

Nuance Time

Yes, at times, America’s foes will work together. China, for example, has continued to trade with Russia throughout the Ukraine War. But the simplest explanation for this is that trade is mutually economically beneficial. Assuming that China trades with Russia because it’s trying to harm America is not reasonable. By any measure, China trades significantly more with Western-aligned countries than with Russia (though US sanctions are encouraging more Russia-China trade). As Eugene Rumer at the Carnegie Endowment put it, “The ‘no limits’ partnership between Beijing and Moscow appears to be a pragmatic, transactional relationship with strategic consequences for both sides, but one that is motivated by complementary rather than identical interests.” One obvious limit of the supposedly “no limits” partnership is that China has not militarily intervened to help Russia in Ukraine.

Yes, at times, the rhetoric employed by America’s foes sounds wicked and crazy, as if motivated by irrational hatred rather than strategy or historic gripe. But don’t take rhetoric at face value! It’s often useful to gin up hatred of an enemy in your domestic populace if you’re in a conflict. Waxing poetic about the evilness of your enemies is a great way to do this.

Most of the time, it’s fairly easy to see why other countries dislike America if you try to view geopolitics objectively. Rarely does one need to posit irrational belligerence or messianic ideology to understand what Xi, Putin, and the Ayatollah are doing. Try to detach yourself from your national loyalty and patriotic sentiments. Try to suppress the instinct that tells you that you and your team are the good guys and that your opponents are the bad guys. While it is true that other countries often do things that reasonably make us consider them “bad guys,” this moralistic framing of geopolitics tends to warp our view of the world and lead us toward poor policy. The things America does certainly render it a “bad guy” as well. By using cognitive empathy and adopting the “point of view of the universe,” we’re better able to consider each country’s security interest and perspective.

An objective, dispassionate view of international relations would note, for example, that America’s effort to change an internationally recognized border by force in the Kosovo War was by seen as provocative by Russia, given its deep historical ties to Serbia. Such a view of international relations might suggest that the US’s support for the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution (which overthrew democratically elected pro-Russian president Yanukovych) would provoke a Russian reaction, since Russia’s military might relies so heavily on maintaining a foothold in Sevastopol (much like how America would react violently if China helped the Mexicans overthrow a pro-Washington regime in Mexico City).

Same goes for the Biden Administration’s moves in 2021 to bring Ukraine into the Western military alliance.8 (According to Zelenskyy, Biden told him before the war that Ukraine would not actually be allowed to join NATO. Biden unfortunately neglected to let the Russian know about this.)

Such a view of international relations would realize that Iran’s nuclear program is likely defensive in nature, given that nukes are a great source of deterrence and that the US and Israel have pursued a policy of maximum pressure on Iran (save the brief period from 2016 to 2018 in which we implemented the Iran Nuclear Deal—thank you Obama!). States that voluntarily give up their nukes (like Libya, Ukraine, and Iraq) lose deterrence and are subsequently subjected to foreign military intervention.

Such a view of international relations would realize that Beijing views America as a dangerous geopolitical actor set on toppling the Chinese government, destroying the Chinese economy, and preventing China from taking Taiwan. Though America ostensibly supports maintaining the status quo in the Taiwan Strait, Washington has been arming the Taiwanese, making it more difficult for the People’s Liberation Army to take the island. Reunifying Taiwan with Mainland China is, of course, Beijing’s number-one foreign policy goal, so America’s actions are undoubtedly perceived as offensive. Further, as I noted above, America has been trying to stall China’s economy development. From the Chinese perspective, this plainly looks like America trying to keep China poor and prevent it from assuming its status as a great nation. We also ought not forget NATO’s 1999 bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade (during the Kosovo War). While Washington claims it was accidental, many Chinese still view it as deliberate. I don’t know enough about the incident to have an opinion about the intentionality, but China’s cynicism is certainly warranted, considering how many times America has attacked civilian targets and lied about it.

I want to emphasize that what’s important here is understanding how America’s adversaries view the world. This is an empirical exercise; it’s not normative. Your understanding of how Russia and China view the world should not be affected by how you think China ought to behave, or whether you think America’s actions have been in accordance with moral principles, or how you think Russia ought to respond to the Westernization of former Soviet republics.9 It should be based on empirical evidence. I encourage my readers to mind the is-ought gap.

In fact, my normative views in many ways align with those of the US foreign policy blob. I don’t like Slobodan Milosevic, Saddam Hussein, Muamar Gaddfi, Bashar al-Assad, or Vladimir Putin. I think all of those guys seriously suck. If I were Ukrainian, I would certainly prefer to be in NATO than be under the Kremlin’s thumb. My allegiance is very much with the colour revolutionaries all across the former Soviet Union. I condemn China’s brutal treatment of ethnic minorities, especially its totalitarian control of Xianjiang. The CCP’s practices there might even be considered cultural genocide.

I don’t want China to conquer Taiwan because the Chinese Communist Party is authoritarian. The Taiwanese are much better off governing themselves democratically. I don’t like the CCP; I’d prefer a world in which the Chinese get to elect their own government. But I don’t let these normative views cloud my judgement about how China, Russia, and Iran perceive America. They quite reasonably views America as a threat.

Perhaps some readers fail to see how I decouple these moral views from my foreign policy preferences (which I haven’t even spelled out yet in this essay, though I’m sure people have their suspicions). I think that the way in which America has gone about promoting liberalism and democracy has had awful consequences, which outweigh the benefits of democratization and liberalization. Firstly, I doubt that the true intent behind most America military interventions is to promote liberalism and democracy. And this ends up corrupting America’s foreign policy endeavours and veering them away from their laudable ostensible goals. And secondly, if America really feels the need to go around spreading Western values, I suggest it do so first at home, and then in its own sphere of influence and among its client states (many of which are quite illiberal and anti-democratic). This would be much easier and less likely to cause nuclear war.

The thing I care most about is preventing global catastrophy from pandemics, bioweapons, nuclear war, AI, and climate change. These issues can only be properly addressed internationally because they involve collective action problems and because viruses and dangerous AIs aren’t confined by borders. So great power competition and cold wars are basically the worst things ever, in my view.

And this is why I bring up the whataboutism arguments—not to justify immoral and illegal actions taken by America’s foes (which I condemn!), but to promote a more impartial view of geopolitics and point out that Russia, Iran, and China are largely motivated by the same kind of plain-old strategic reasons that motivate America. Once you recognize that the actions of Russia, China, and Iran are often shaped by the geopolitical circumstances that America largely created (being the sole superpower for a few decades), you can no longer chalk up their behaviour to pure evil. And once you recognize that America’s foreign policy has been far from benevolent, the rest of the Good Versus Evil geopolitical worldview crumbles to pieces. This eliminates the apocalyptic argument that says America must seek its enemies’ total destruction.

America Bad

A common critique of the leftist/realist/libertarian/anti-interventionist view of geopolitics is that it merely criticizes whatever America does, and lets other countries off the hook by “denying their agency.” My view is that America ought to consider the ideologies, incentives, and interests that shape other countries’ behaviour and make policies based on the expected consequences of its actions considering those constraints. This seems more prudent than America simply doing whatever it wants and hoping other countries will exercise their “agency” to accommodate it.10

The other common critique is that we’re “parroting Kremlin/CCP talking points” or “supporting terrorism,” but this is just an ad hominem. If they get to have that logical fallacy, then we get to have whataboutism. And for the reasons I outlined above, what often looks like whataboutism is actually not a logical fallacy but a useful critique of American foreign policy.

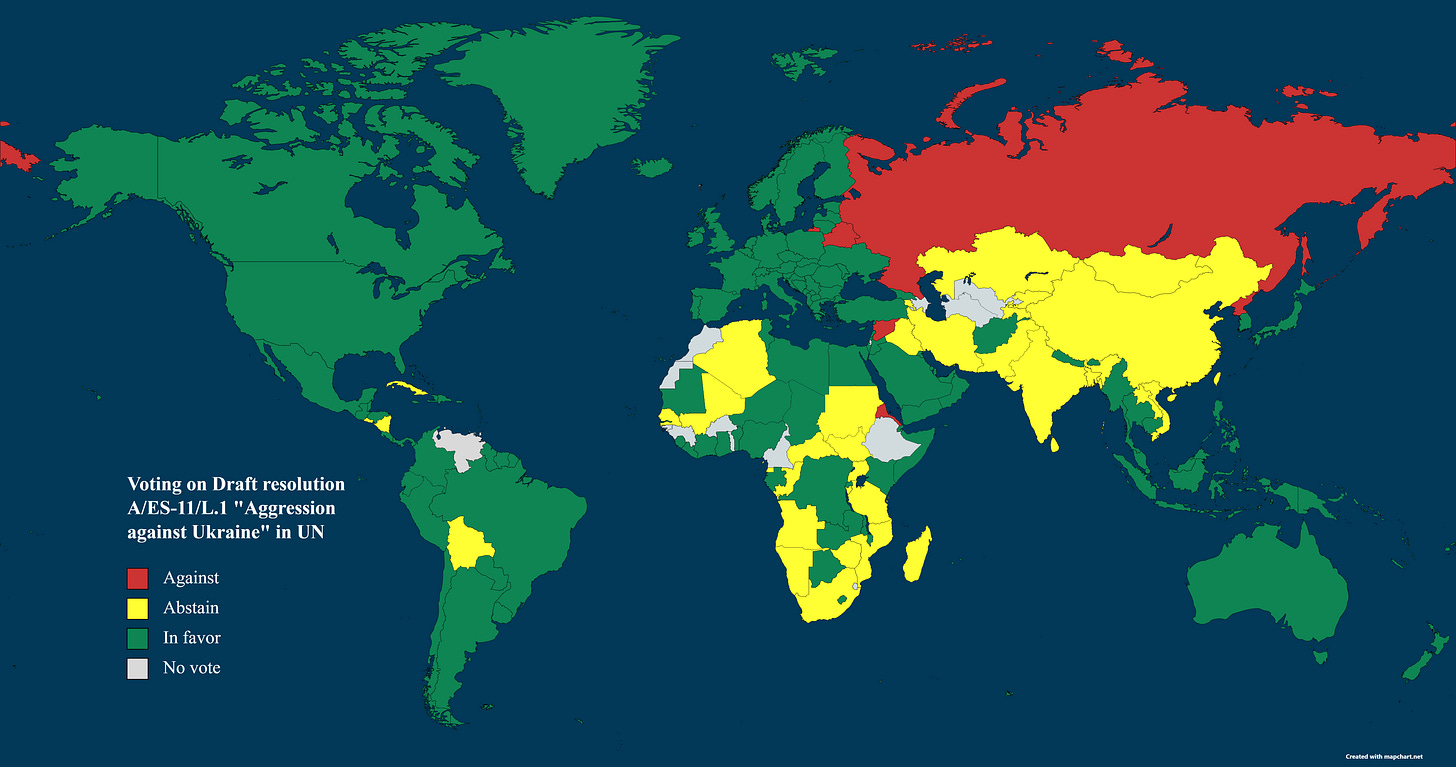

Lastly, it’s worth noting that America’s transgressions give cover to other countries’ actions. When America criticizes Chinese and Russian aggression, Xi and Putin can point out US hypocrisy, which undermines the American critique in the eyes of many other countries. This might be why so much of the world was uninterested in supporting America’s side in the Ukraine War, viewing it as just another imperialist endeavour. This is a shame! It would have been nice to assemble a larger bloc of countries to support Ukraine back in 2022 against Russia’s unjustifiable and criminal invasion.

Regarding American hypocrisy, former US ambassador to the USSR Jack F. Matlock, Jr., wrote this in Responsible Statecraft:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was initiated by President Putin because he believed, with reason, that the United States was trying to draw Ukraine into a hostile military alliance. Therefore, in his eyes it was provoked. In 2003 the United States invaded, devastated, and occupied Iraq when Iraq posed no threat to the United States. So now, how is it that the U.S. and its allies are conducting an all-but-declared war against Russia for crimes they themselves have not only committed, but have committed with less provocation? The pot is calling the kettle black and trying to damage it.

Even if you refuse to buy this narrative—and please don’t tell me you think NATO is a purely defensive alliance—you must recognize that Biden should have been able to predict that the Russians would see things this way. A bit of self-awareness and whataboutism could have helped him with that.

In the 1990s, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, America practically ruled the world. It had enormous norm-setting power and could have chosen to enthusiastically endorse international law and the principle against trans-border aggression. It briefly did this for the Gulf War—it was a legal war, authorized by the UN Security Council. But the US decided instead to pursue a policy of primacy, where American forces would continually intervene abroad wherever and whenever Washington wanted. The most prominent manifestations of this in the ’90s were Clinton’s bombardment of Iraq in ’98 and the NATO bombardment of Serbia in ’99. And then things really hit the fan under W. Bush and Obama.

Rather than promoting a liberal rules-based order in which use of force was limited by the UN Charter, the US endorsed a might-makes-right order in which the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. But the unipolar moment is over. I’m afraid now that America is no longer the only strong country, it’s reaping what it sowed.

I think the NATO bombing of Serbia during the Kosovo War was wrong partly because it did little to prevent ethnic violence (and perhaps provoked more of it) but mostly because ignoring international law made America a complete hypocrite and contributed to the destruction of the rules-based international order.

Not to mention America’s history of intervening in domestic Iranian affairs.

Trump seems to be undoing this, at least regarding Russia, and pursuing more of an incoherently expansionist foreign policy.

Or maybe America acts on pure benificence and freedom juice.

I believe the “rules-based international order” is merely a tool to disguise American domination.

I don’t think CRINGE is America’s greatest threat; Smith thinks that. I think pandemics, bioweapons, AI, nuclear risk, and climate change are America’s greatest threats, and the only way we can address them is by working with China and Russia (and other major powers).

It’s also worth noting that Iran’s proxies and China have never taken military action anywhere near North America. Though these actors are hyped up as the greatest threats to the security of the West, this very simple observation is often ignored in mainstream media.

Technically, it was unlikely Ukraine would officially join NATO; European countries (and probably the US Senate) wouldn’t allow that. However, in 2021, Biden signed the US-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership which de facto made Ukraine a Western ally (without actually extending it any security guarantees). As Andrew Day put it, NATO was in Ukraine but Ukraine wasn’t in NATO. The charter even said, “The United States and Ukraine … [e]mphasize unwavering commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, including Crimea…” I certainly agree that Ukraine has the right to Crimea. But to the Kremlin, this sentence obviously looks like a commitment by the US to retaking Crimea by force and kicking the Russian navy out of Sevastopol once and for all.

In October of 2022, the CIA warned that an attempted recapture of Crimea by Ukrainian forces could provoke a nuclear response, the likelihood of which they said might rise to 50% or even higher. A few months later, in January of 2023, the White House was reportedly warming to the idea of a campaign to recapture Crimea. This is one small example of what I would call extremely imprudent foreign policy from the Biden team.

Regarding the Westernization of former Soviet republics, here’s an abridged list of people who argued that expanding NATO eastward and ignoring Russian security interests—especially regarding Ukraine—would lead to war:

US ambassador to the USSR George Kennan

US ambassador to Russia and CIA director Bill Burns

CIA director Stansfield Turner

US ambassador to the USSR Jack Matlock

US ambassador to the USSR Arthur A. Hartman

UK ambassador to Russia Roderic Lyne

US ambassador to Poland Richard T. Davies

US ambassador to Bulgaria Raymond L. Garthoff

US ambassador to NATO Stanley Resor

US secretary of state Henry Kissinger

US secretary of defence Robert McNamara

US secretary of defence William Perry

US secretary of defence Bob Gates

US secretary of the navy Paul Nitze

US secretary of energy James D. Watkins

US state department director of policy planning Morton Halperin

US deputy national security advisor Carl Kaysen

US undersecretary of the army David E. McGiffert

Top CIA Russia analyst George Beebe

US National Security Council Soviet Director Richard Pipes

US General Robert E. Pursley

Advisor to Ukrainian president Zelenskyy Oleksiy Arestovych

Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Editor of Foreign Policy C. William Maynes

Editor of National Interest Owen Harries

Brookings director of foreign policy John Steinbruner

Linguist and political scientist Noam Chomsky

Political scientist John Mearsheimer

Russia scholar Stephen Cohen

Russia expert Susan Eisenhower

Russia expert Vladimir Pozner

Russia expert Robert Service

US senator Bill Bradley

US defence undersecretary Fred Ikle

US undersecretary of the air force Townsend Hoopes

Senate Armed Services Chair Sam Nunn

Senator Gordon Humphrey

Intelligence officer and National Security Council member Fiona Hill