Stop pining for pre-Trump politics

The neoliberal consensus sucked, and shifting wholesale to the centre will lose Harris the election.

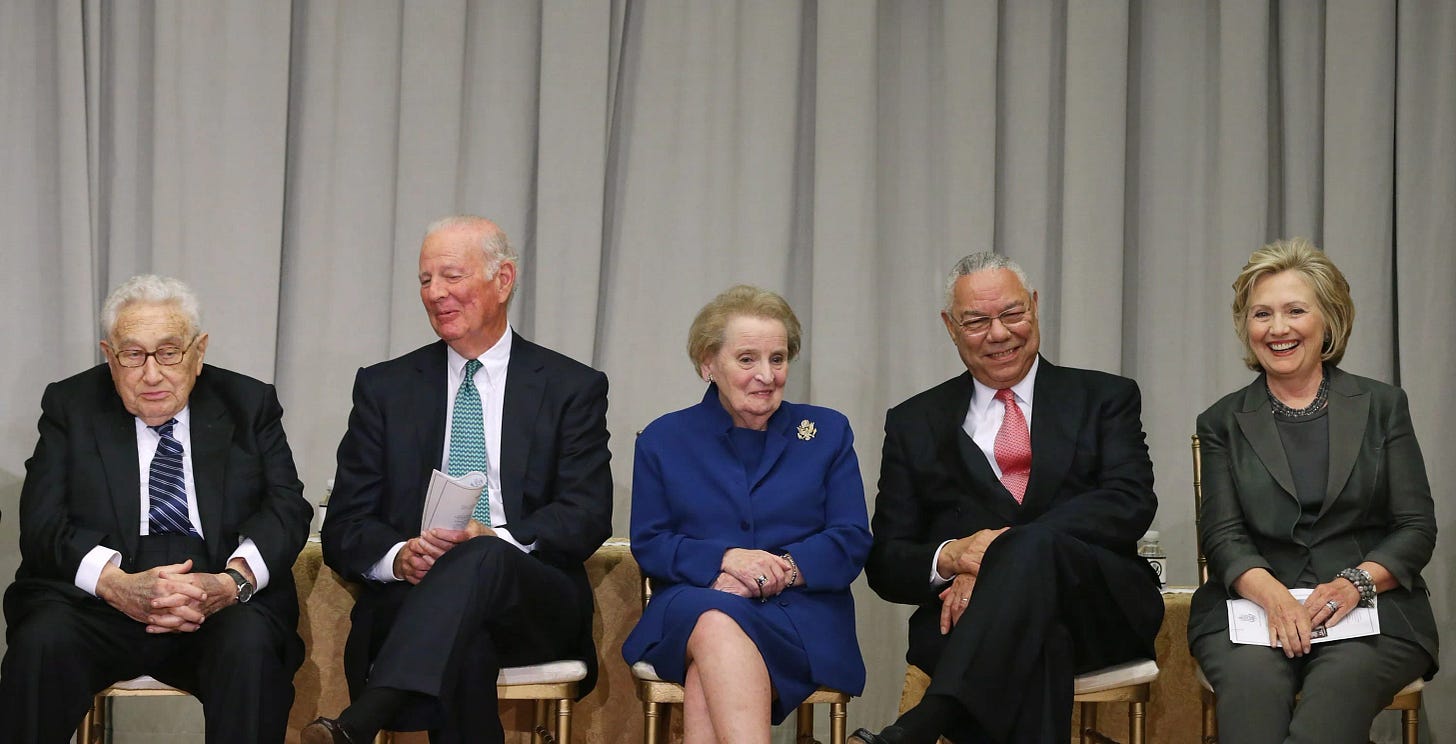

I often hear pundits express nostalgia for American politics before Trump: there were the reasonable Democrats, who wanted minimal economic reform and a bit of social progressivism; and there were the responsible Republicans, who wanted fiscal conservatism1 and family values.2 And everyone supported wars in far-away lands, keeping the US-led liberal world order intact. These two parties complimented each other, creating a perfect milquetoast synthesis, embodied by the likes of Mitt Romney, Barack Obama, Colin Powell, Hillary Clinton, and John Boehner.

I’m over simplifying a bit—the Democrats were definitely still the good guys: Obama gave millions of people healthcare and kinda ended the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Regardless, I lack a longing for this era of American politics, when the discourse on economic issues was restricted to a moderate zone: to the right of social democracy and to the left of anarcho-capitalism. The social safety net was weak, inflation was considered more of a threat than unemployment, and Wall Street types like Robert Rubin (Goldman Sachs), Larry Summers (D. E. Shaw & Co.), Jack Lew (Citigroup), and Timothy Geithner (Warburg Pincus) filled important economic appointments, even in Democratic administrations. In their meticulously researched book Where Have All the Democrats Gone? Ruy Teixeira and John Judis write the following:

Obama balked at populist appeals. Instead, he cautiously settled for half-measures and continued the Democrats’ devolution into a party with only a tenuous hold on the working-class voters who had once sustained it.

The discourse on economic issues, though restrained, wasn’t nearly as rigidly contained as the discourse on foreign policy, whose left-wing (Pod Save the World et al.) included Iraq War sceptics who nonetheless supported regime change in other Middle Eastern countries (remember Obama’s interventions in Libya and Syria?) and whose right-wing (Victoria Nuland, David Frum, Bob Kagan, etc.) included those who wanted to spread freedom across the globe through eternal “preventive” war.

The issue with this style of New Haven and Cambridge politics—in which neoconservatives line the pockets of Raytheon and Boeing execs by getting America into forever wars and neoliberals line the pockets of BlackRock and JPMorgan Chase execs by deregulating the financial sector and crushing labour3—is that it screws over lots of Americans. And when a huge swath of the populace is upset, blaming it all on immigrants becomes an appealing political message. It didn’t matter that most of the screwing was done by the Republicans: Democrats hadn’t done enough to convince working-class Americans—particularly white, rural Americans—that they would help them. Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign spent a lot of time labelling half the country as deplorable racists, heavily featured identity politics (I’m with HER), and didn’t present an economic platform that won over Americans whose manufacturing jobs had gone overseas. Teixeira and Judis discuss how Bernie Sanders represented an economic populism that could have given the Democrats the win in 2016:

By criticizing Clinton’s subordination to neoliberal, third way, or Wall Street economics, Sanders had exposed a flaw in Clinton’s and Democrats’ promise to voters. The policies that had begun under Bill Clinton and been followed, more or less, by Obama had not delivered prosperity, particularly to those towns and regions that depended on manufacturing or mining. And there was no reason to believe that Clinton would diverge from those policies. Trump was able, in effect, to piggyback on the case that Sanders made against Clinton’s and the Democrats’ economics. And that challenge was an important reason for Trump’s political success against her in the industrial Midwest.

By refusing to depart from the pre-Trump political status quo—which was dominated neoliberal economic policy in both parties—Democrats lost the presidency and the Senate (Republicans already had the House). Donald Trump kicked this political equilibrium in the balls, and we’re not going back. In response to Trump’s insane economic policies (trade wars, a perniciously anti-labour National Labour Relations Board, tax cuts for the wealthy, etc.) and populist rhetoric, Democrats have had to get their act together. Joe Biden put pro-union people on the National Labour Relations Board, banned noncompete agreements, increased the number of people eligible for overtime pay, and signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which will benefit poor Americans and address the unfair skewing of the wealth distribution.

These policies are good and popular, and Democrats need to keep pursuing them. More Republicans support than oppose Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Seventy-one percent of Americans support unions. Sixty percent of Americans think “the government should raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans” to address wealth inequality.

More Americans consider themselves foreign policy doves than hawks, and far more Americans think the US should not take a leading role in solving all the world’s problems than think it should.

Let me be clear: I’m not saying Democrats should double down on every issue, pursuing ideological purity just as MAGA Republicans do. I agree with Johnathan Chait here:

On issues where progressive values are unpopular, and there are several, Democrats should definitely shy away from progressive values. For example, their stance on socialism, which is an extremely unpopular concept, should not be to liken it to neighbourliness, but to say it’s bad and promise not to do it.

Yes, Democrats should move to the centre in their messaging on certain issues. From now until Harris gets into office, Democrats, please don’t talk about DEI, defunding the police, or transgender healthcare. (And once she’s in office, don’t pursue maximally leftist policies on these issues.) Also, I’m happy to moderate on immigration—an issue where progressives like me are really out of synch the average American—even though I think immigrants are largely beneficial to their host countries.

The way Democrats can win the election in November and keeping winning elections is not by pivoting to the centre on economic or foreign policy (as some pundits like Johnathan Chait want)—that would further the worrisome political realignment the GOP and Dems have gone through whereby the working-class increasingly votes Republican. Instead, they should focus on delivering for labour, closing the wealth gap, and withdrawing American troops embroiled in disastrous conflicts overseas.4

This was always a mind-numbingly bald-faced lie.

No gay people.

I don’t actually think American politics is overtly corrupt in the way that some might interpret this to mean. E.g., I don’t think Lockheed Martin explicitly pays off the Atlantic Council to lobby Congress for more military spending; I just think that the people in these institutions (Congress, military contractors, international affairs departments at fancy universities, hawkish think tanks, etc.) hold a similar ideology and converging interests, giving the wealthy extra influence on policy.

Did you know there are American troops in Syria right now, against the wishes of the Syrian government and thus in violation of international law? Is fighting a proxy war with Russia and Iran in Syria really an integral national security issue?