Neoliberalism and the Future of the Democratic Party

And some data on what Americans actually think

If you like what I write and want other people to see it, please like, comment, and share!

The Democratic Party is the least popular it’s been and the Republican Party is the most popular it’s been since 2008, according to a recent Quinnipiac poll. 31% of voters have a favourable view of the Democrats and 57% have an unfavourable view. This is “the biggest favorability advantage the Republican Party (43 percent) has held over the Democratic Party (31 percent) since the Quinnipiac University Poll began asking these questions.”

Don’t fret though, the newly elected leader of the party Ken Martin says that the party doesn’t need to change its message to voters: “Anyone saying we need to start over with a new message is wrong,” he said. “We got the right message.”

Right now on the left, pundits are slinging takes like wild to try to diagnose the current disaster we inhabit and prescribe what we ought to do to get out of it. A lot of the fighting has been about whether Democrats are unpopular due to economic issues (i.e., they haven’t been progressive enough and neoliberalism was bad) or social issues (i.e., they’ve been too progressive and wokeism was bad).1 Liberal pundits are kinda coalescing into two camps around these views, which in a sense I think is bad because the truth is probably a nuanced mix of the two views and left-on-left violence probably harms the Democrats. But I support public discourse and debate, and trying to understand the root causes of the unpopularity of the Democratic Party is crucial.

The issue is that it’s pretty difficult to empirically determine why voters do what they do and believe what they believe. Do they vote on policy? messaging? candidates? pure vibes? Later on I have some preliminary thoughts about this, but I’ll give some background on the current debate:

The Great Battle of Neoliberalism

has proposed a common-sense Democratic manifesto emphasizing the need to abandon identity politics that I think is pretty good. Chris Murphy, a senator from Connecticut that I like a lot, wrote a long Twitter thread a few days after the 2024 election emphasizing the need to break with neoliberalism. Bernie Sanders joins Chris Murphy in mostly blaming economic issues for Democrats’ plight, tweeting, “It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working class people would find that the working class has abandoned them.”DNC Party Chair and former corporate lobbyist Jaime Harrison referred to this as “straight up BS,” arguing that Joe Biden was the most pro-worker president since FDR. Glen Greenwald responded to Harrison thus: “You and the corporatist and militarist party you lead just got your asses kicked all up and down the US, because Americans see that you only care about enriching yourselves at the corporate lobbying trough.”

, it seems to me, straddles the two camps but emphasizes cultural over economic issues: “You want more neoliberalism or less neoliberalism, whatever. A lot of Democrats’ problem is that voters see through the surface rhetoric and recognize that Democratic elites see them as plebes and look down on them.”2To a certain extent, these hot takes go to show that pundits will interpret everything as confirming their theory of how the world works and discrediting that of their opponents, no matter what happens. Just looking at polling data isn’t enough to tell us whether social or economic issues are more important to voters and whether Democrats’ embrace of “neoliberalism” doomed the American left.

Establishing causality is hard, and it’s lacking in mainstream political discourse. It’s all about making causal inferences from observational data, data that doesn’t inherently tell you the reason people do what they do. The what is easy to figure out, it’s the why that’s hard.

Nuance time

Neoliberalism is an extremely vague term that people usually just use to deride whatever economic policy they don’t like. On one hand, neoliberalism has been used to refer to Thatcherite and Reaganite market fundamentalism, whereas on the other people like Brad Delong and Matt Yglesias have used it to refer to basic left-of-centre capitalism with a social safety net.

Fellow Substacker

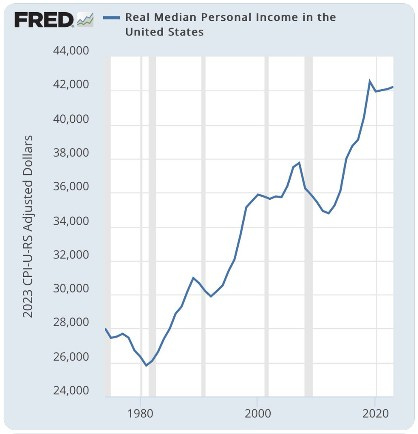

, who’s writing I often enjoy, joined the Great Battle of Neoliberalism with a blog entitled “Some Democrats Think the Disease Is the Cure.” He derided the economic populists on the left of the Democratic Party, saying the argument that “Democrats have abandoned economic interests of the working class” is “completely and demonstrably false.” I’m not sure this is true, and in reality the question is more complicated than he portrays it.To “completely and demonstrably” show that Democrats’ embrace of neoliberalism was good, Maurer provides the following graph of real median personal income during the neoliberal era:

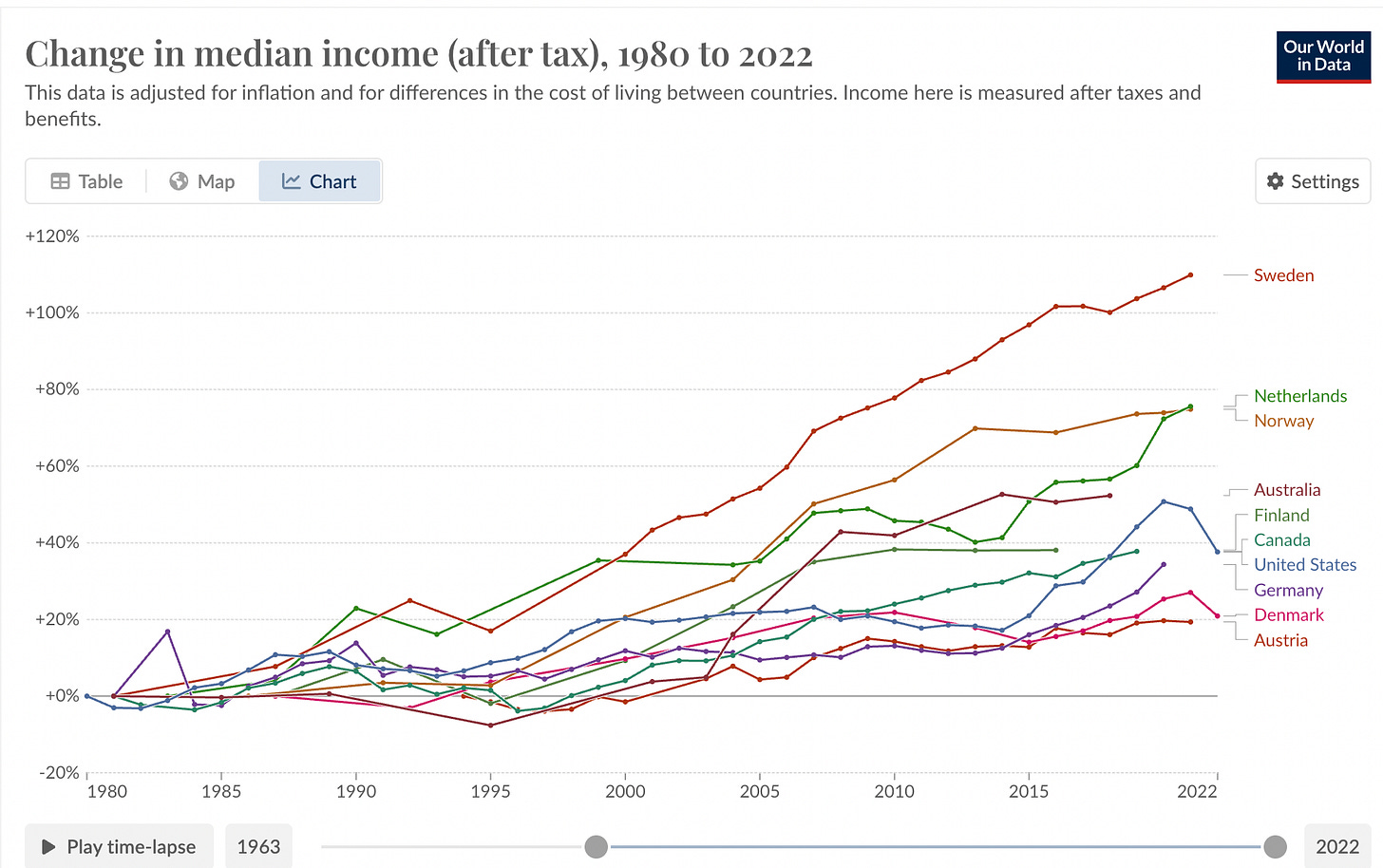

Just showing that Americans’ incomes have gone up from 1980 to present is far from sufficient to prove the claim that neoliberalism is a policy platform Democrats should run on. This graph is entirely uncomparative because it doesn’t look at what income growth was like before neoliberalism or in places with more left-wing economic systems. Check out this graph3:

The above graph makes me think perhaps the post-war era of strong unions, super high top marginal tax rates, and strong GDP growth was better for working Americans than the post-’70s era of free-market fanaticism.

And it’s not clear that the neoliberal American economy outperformed social democratic economies. (It’s also not clear from the below graph that social democracy is definitively better than neoliberalism, to be sure.) America is near the bottom of the pack here, beating out Germany and Denmark but losing badly to Sweden, the Netherlands, and Norway.

I’m merely presenting correlations, not trying to claim causation. But that applies equally to Jeff Maurer’s graph of median personal real income. There are lots of ways of empirically measuring the performance of an economy, and it’s basically impossible to analyze the counterfactual in economics, which is what makes social science hard (and interesting!). Many economists have devoted their life’s work to trying to figure out what mixture of state and market leads to the best outcomes, and one should not formulate one’s economic worldview based on a couple graphs.4

The point is that it’s not clear neoliberalism was good for Americans, and it’s not clear it was better than other economic policy regimes. Some neoliberal policies, like free trade, were probably good on net because they provided Americans with cheaper consumer goods. Other neoliberal policies, like the deregulation of financial markets done under Clinton and W. Bush, were probably bad (think Great Recession). I also think it’s clear that inequality soared under neoliberalism, and there are some very good arguments as to why inequality is bad, even if you don’t believe it’s inherently wrong. Check out Francis Fukuyama’s latest book Liberalism and Its Discontents for a thorough critique of neoliberalism (and identity politics).

As I’ve written in the past, I think there’s a convincing case to be made that free trade harmed Americans who lived in manufacturing-heavy areas like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. And while these communities are not the economically worst off compared to other demographics (sociotropically), they are the worst off compared to their past selves (retrospectively). These communities delivered Trump his win in 2016 in large part because he rejected free trade, a core tenet of neoliberalism.

I also think neoliberalism’s support for neoclassical economics has probably harmed Democrats. For example, the economic doyens of the Democratic Party tend to be deficit hawks, tend to favour a privatized healthcare system, and tend to view inflation as a greater threat than unemployment. If Democratic presidents had sought policy advice from left-leaning economists like

5 and James Galbraith rather than Wall Streeters like Larry Summers and Robert Rubin, they might have pushed for a greater stimulus following the great recession, which could have sped up the recovery and increased employment.6 A Keynesian Democratic Party might have even taken advantage of the decade of super low interest rates in the aughts to invest in public infrastructure, education, and a green energy transition, which would directly create jobs and have long-term multiplicative economic effects. If only!Lastly, Maurer implied that voters’ rejection of Harris in 2024 was because Biden had opposed neoliberalism.7 I think this argument is super silly firstly because I’m not convinced Biden made a clean break from neoliberalism and secondly because it makes no effort to deal with all the other confounding variables that could have influenced the election, like inflation and Biden’s old age.8 Maurer even tries to briefly argue that it was the economic populists on the left wing of the party and their MMT9 policies that caused inflation and thus Harris’s downfall. I think this is ridiculous for a bunch of reasons that I’ll address in-depth in a later post. Check the footnotes for further discussion.10

In any case, my liberal daydreams are certainly not evidence that Democrats lost the working class due to neoliberalism. If anything, Democrats were way more supportive of labour in the last few decades than Republicans, and one has to wonder whether too-conservative economic policy can be the reason the working class shifted from the Democrats to the even-more-conservative Republicans.

But it could be true that voters are fed up with the Dems because they claim to represent the economic interests of the working man while not doing enough to actually deliver for him. Perhaps the Republicans, with their hyper-nationalist rhetoric and social grievances, were able to connect with those discontented voters.

What we do know

We have lots of data that tells us what Americans think about social and economic issues. At the very least, I think Democrats should consider addressing issues that large majorities of Americans agree on. The Republican Party will never do this because it’s shockingly corrupt and incompetent and beholden entirely to the economic interests of the handful of oligarchs who hang around Mar-a-Lago.

There are a few key economic issues where I think most of the Americans are to the left of the Republicans and the Democrats:

Most Americans believe the wealthy have too much influence on politics. 80% of Democrats and 83% of Republicans believe “the people who donated a lot of money to . . . political campaigns . . . have too much influence when it comes to the decisions that members of Congress make.” Perhaps campaign finance reform could be a winning issue. Voters largely hold left-coded view on money in politics.

Most Americans support organized labour. 67% of Americans approve of unions, and Americans overwhelmingly sympathize with workers over employers when it comes to labour disputes.

Most Americans want to tax the rich. About two-thirds of Americans think large corporations and people making over $400,000 a year should pay more in taxes. Depending on how pollsters word the question, between 60 and 74% of Americans want to raise taxes on the wealthy.

Most Americans think healthcare is the responsibility of the government. 59% of Americans think it is the responsibility of the federal government to ensure all Americans have access to healthcare. 67% of Trump voters have a favourable view of Medicaid, which provides healthcare to low-income Americans. Republicans politicians want to cut it.

Social Issues

Democrats probably need to distance themselves from identity politics/wokeness. Matt Yglesias was right when he said that Democratic Party employees should all put sticky-notes on their laptops that read, “the median voter is a 50-something white person who didn’t go to college and lives in the suburbs of an unfashionable city.”

Lots of Americans are suspicious of the BLM Movement. 40% of Americans view it negatively while 38% view it positively.

Americans on net disapprove of race-based affirmative action for admission to selective universities. 50% disapprove while 33% approve.

Most Americans are not too hot on “woke gender ideology” or whatever Fox News is calling it these days. 60% of Americans say gender is determined by sex assigned at birth.

Very few Americans use social justice terminology. Lots of Americans are aware of terms like “intersectionality,” “emotional labour,” and “implicit bias”—but they don’t use them.

Also note that white American progressives, in particular, hold many political views that are to the left of most Americans, including racial minorities:

Maureen Dowd put it thus:

Democratic candidates have often been avatars of elitism — Michael Dukakis, Al Gore, John Kerry, Hillary Clinton and second-term Barack Obama. The party embraced a worldview of hyper-political correctness, condescension and cancellation, and it supported diversity statements for job applicants and faculty lounge terminology like “Latinx,” and “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, People of Color).

This alienated half the country, or more.

Voters are not rabidly anti-woke

Most Americans are antiracist. Majorities of Asians, Hispanics, blacks, and whites in America believe in systemic racism.

Most Americans don’t hate DEI. 52% of U.S. workers say that, in general, focusing on increasing, diversity, equity, and inclusion at work is mainly a good thing. 21% think it’s mainly a bad thing.

Most Americans aren’t transphobes. 64% of Americans favour or strongly favour laws or policies that would protect trans people from discrimination in jobs, housing, and public spaces.

It’s important to note that we can’t infer from these data that people would vote for Democrats if only they adopted policies that most people agreed with. There’s probably lots of other stuff that influences voter behaviour, and especially considering how uninformed most voters are, I doubt policy is as important as most pundits think it is.

Don’t forget about war!

Foreign policy is, in my opinion, the most important political issue. America gets to decide whether or not millions of people will die through its foreign policy. Foreign aid, a tiny fraction of the federal budget, has saved millions of people from preventable diseases in the developing world. The American military, about 13% of the federal budget, has killed millions of people abroad in unnecessary and illegal wars that are also devastating for the families of fallen American service members.

What’s more, going around the world and illegally intervening in foreign countries to try to shape them in our image makes other important geopolitical actors—Russia, China, the EU, and rising powers like Brazil and India—trust America less. And by constantly breaking international laws and norms, the US has undermined the most basic tenets of international governance that were meant to prevent a third world war. If we’re ever going to address AI-, nuclear-, bio-, and climate-risk, we will need to do so globally, because these challenges all entail the collective action problem.

So that’s why having a more restrained and less militaristic foreign policy is important. But how can it help Democrats electorally? Well, a majority of Americans agree with me—not Hillary Clinton or George W. Bush—on foreign policy.

Americans are restrainers, not interventionists. ~60% of Americans think the United States “should not take the leading role among all other countries . . . in trying to solve international problems.”

Americans are not Ukraine hawks. “57% of likely American voters support the U.S. pursuing negotiations as soon as possible to end the war in Ukraine, even if it means Ukraine making some compromises with Russia.” And 80% of Americans think the U.S. should either make aid to Ukraine conditional, reduce aid, or cut aid to Ukraine entirely.

Americans are not Israel hawks. 61% of Americans think the US should not send weapons to Israel. And 57% thought Biden should have encouraged Israel to either decrease or stop its military actions in Gaza.

Americans are not Taiwan hawks. Only 30% of Americans think the U.S. should defend Taiwan against a Chinese invasion given the potential costs. 44% feel that avoiding war with China is more important than Taiwan’s political autonomy.

Americans are NATO-sceptical. 39% of Americans disagree (compared to 27% who agree) with the position that the U.S. should defend NATO countries that miss their defence spending obligations.

Americans are worried about U.S. troop presence in Syria. 56% of respondents are “very worried” or “somewhat worried” the presence of U.S. troops in Syria could escalate into a broader conflict in the region. Note that this was before the recent regime change in Syria.

Americans regret the Iraq War. In 2019, 62% of Americans thought the Iraq War was not worth fighting.

Americans don’t believe in preventive war. 65% of Americans say that the US military should not attack another country unless attacked first.

What’s more, Trump used foreign policy to gain an edge on Democrats. While the Democrats embraced war hawks Dick and Liz Cheney, JD Vance derided them, saying they “want to start wars … all over the world” (which seems true) and “Donald Trump is the candidate of peace” (which is not true). Trump effectively capitalized on Muslim Americans’ frustration with US foreign policy, painting Harris as a pro-Israel hawk. (She didn’t really distance herself from Biden on the issue, so Trump was right on this.)

Political scientists Douglas L. Kriner and Francis X. Shen studied the impact of the Bush-Obama wars on the 2016 campaign, and found that “there is a significant and meaningful relationship between a community’s rate of military sacrifice and its support for Trump. … [I]f three states key to Trump’s victory—Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin—had suffered even a modestly lower casualty rate, all three could have flipped from red to blue and sent Hillary Clinton to the White House.”

Trump really was speaking to the forgotten and ignored parts of America, when it came to foreign policy. Democrats have never strayed from the view that America is a uniquely good and powerful actor in the world and that it ought to intervene abroad militarily to promote its worldview. And though is many ways Trump is more militaristic than the Democrats, at the very least he paid lip service to restraint and used non-interventionist themes in his messaging. On the other hand, Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden both voted for the Iraq War! For a great essay on the failures of American foreign policy, see Foreign Policy Elites Fail Upwards by

.Let’s not screw this up

There’s plenty of space on important issues where Democrats can easily align themselves more with voters, they just need to actually do it. Again, I’m not sure to what extent policy informs politics, but I really doubt it would be harmful for the party to start adopting views that most Americans hold.

It doesn’t seem like moving to the centre on economic issues—becoming more neoliberal—is the way to go, despite what Jeff Maurer writes. But Democrats are clearly to the left of most Americans on immigration and other social issues. I think it’s possible that Democrats could effectively win back a lot of swing voters who have conservative social views by merely improving their economic (and foreign) policy. This hinges on the theory that economic dissatisfaction drives cultural backlash.11

Perhaps voters feel disenchanted and frustrated due to worsening inequality and the impression of economic stagnation, so they lash out at cultural elites. In other words, maybe if we got rid of the economic issues, people would stop caring about the cultural issues.12

And regarding the big debate over neoliberalism vs. economic populism, I wish pundits would be more specific about what they’re talking about. Within both economic populism and neoliberalism there are good and bad and popular and unpopular policies, and those subcategories don’t always align. It could be the case that neoliberal policies were largely good but portrayed poorly in the media thus were unpopular (or vice versa). Also it could be the case that unpopular policies that we would never try in America (like democratic control of large firms) would be extremely good and popular if we implemented them, but we’ll never know.

I say it’s better to stick to the issues I wrote about above, where we have robust data showing what Americans really think.

Actually, lots of pundits are mostly concerned with yelling at team red rather than trying to whip team blue into shape. As I’ve written before, it’s best not to fixate on things that are outside our influence. We ought to take the brazen vileness of the Republican Party as a given and figure out how to work around it.

The graph comes from Jason Furman’s 2021 testimony to Congress on economic disparities and the economic challenges facing American families. It’s worth reading in full. Furman is an economist at Harvard and former chair of Obama’s council of economic advisors. If this is the stuff that really floats your boat, you’ll surely like my interview with Claudia Sahm, who was also on Obama’s council of economic advisors.

Which countries grow economically and which stay poor? Good question. See answer here.

Speaking of Dean Baker and how the Democrats are unpopular with the working class, check out what Dean wrote in 2016 about how the upper middle class often supports policies that harm workers, even though they like to think of themselves as progressive.

Which helps all workers by giving them more bargaining power!

It seems to me that Harris kinda ran to the right of Biden on economic policy, barring a weird foray into price gouging controls.

What I mean is that voters probably lost trust in the Democratic Party broadly when it covered up Biden’s age, which led them to distrust Harris, too.

Signal thunder and lightening and evil cackling!

In brief, I think the ’21-’22 rise in prices was mostly caused by commodity price shocks (and perhaps collusion by price-setting firms) and not by a general devaluation of the currency due to excess fiscal stimulus and an expasion of the monetary base (that’s the kind of inflation Milton Friedman was talking about when it said it was “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”) We can deduce this because (a) the price shocks coincided with two massive disruptions to global supply chains in the Ukraine War and Covid; (b) prices went up worldwide, not just in countries with large fiscal stimulus packages; (c) high unemployment was not necessary to bring down prices; (d) firms brought home larger-than-expected profits which they could justify by pointing to Covid and the Ukraine War; (e) the Biden stimulus helped fill and did not overcompensate for a huge GDP output gap; and (f) prices fell on their own, independent of monetary policy. These are my subsequent reasons for F:

Inflation peaked in June 2022, only three months after the Fed started raising rates and when rates had only been raised by 75 basis points.

High interest rates plausibly contributed to inflation by making it more difficult to bring supply back online. This is particularly important due to the weird way housing is included in CPI.

High interest rates plausibly contributed to inflation by effectively adding hundreds of billions of dollars to banks’ reserves, which they in turn lent out. This is because the Fed had to transfer massive amounts of money to commercial banks as interest on their reserves at a time when commercial banks held unprecedented amounts of money in reserves at the Fed. This is because the Fed bought tons (over three trillion dollars’ worth) of government bonds and securities from commercial banks during the depths of the Covid recession to try to juice the economy.

These graphs present evidence for the opposite view, that fiscal stimulus and low unemployment contributed to inflation:

For more, see this article by James K. Galbraith.

By analyzing populist politics and the disparate geographic effect of two economic shocks in Europe (Chinese import penetration and the 2008 financial crisis), this report from the European Centre for Economic Policy Research found that “the cultural backlash against globalization, traditional politics and institutions, immigration, and automation cannot be an exogenous occurrence; it is driven by economic woes.”

For more evidence of the cultural backlash theory in America, see John Judis and Ruy Teixeira’s excellent book Where Have all the Democrats Gone?

Perhaps the opposite is true: maybe voters are mostly upset about immigrants, and if we kicked out all the immigrants they would abandon their populist economic views. I haven’t seen any evidence to back up this view.

Really good stuff. Loved all the graphs. I am still so unclear on whether or not this (stances on economy, woke, foreign policy) is all just confirmation bias or not. If everyone broadly agrees that corruption is bad— why does Trump win? My theory is that most voters are vibes-based. My question to you: which policy decision would cultivate the best vibes? (I personally think it is public healthcare)