AI Is Smarter and More Creative than You

And it might destroy the world (contra Christopher Beha)

Christopher Beha’s essay “AI Isn’t Genius. We Are.” (published in the New York Times in December1) argued that now might “be the time to retire our worst fears about the technology.” Beha is a writer and editor I admire, especially for his stewardship of Harper’s, my favourite magazine. But he’s dead wrong about AI.

Though Beha does note that there’s a “quite reasonable anxiety surrounding the potential social and economic disruption of a powerful new technology,” what he fears most is not the destruction of the world, the extinction of humankind, or the transformation of the economy into dystopian techno-feudalism in which inequality is locked in for eternity and AI moguls wield their superhuman power to control the universe. Those things are what I fear. Rather, Beha’s essay focused on the fear “that a digital machine might one day exhibit—or exceed—the kind of creative power we once believed unique to our species.”

What Beha fears most not only is benign in comparison to other AI risks but has already come to pass. AI is smarter and more creative than us. It keeps blowing past performance benchmarks that people recently regarded as absurdly difficult to pass.

For example, in 2016 AlphaZero surpassed all human knowledge about the strategy game Go and beat its best players, which most experts regarded as astonishing, given how open-ended and abstract Go is. That was nine years ago. AlphaFold solved the protein folding problem, which Nobel-prize-winning biologist Venki Ramakrishnan called “a stunning advance … [that] occurred decades before many people in the field would have predicted.”

More impressive still, AI is improving its general intelligence, not just its technical abilities. ARC-AGI is a challenge made by François Chollet that’s meant to assess an AI’s ability “to adapt to new problems it has not seen before and that its creators (developers) did not anticipate.” In other words, can the AI acquire news skills outside its training data? Well, chain-of-reasoning LLMs are really good at Chollet’s test.

As friend of the blog

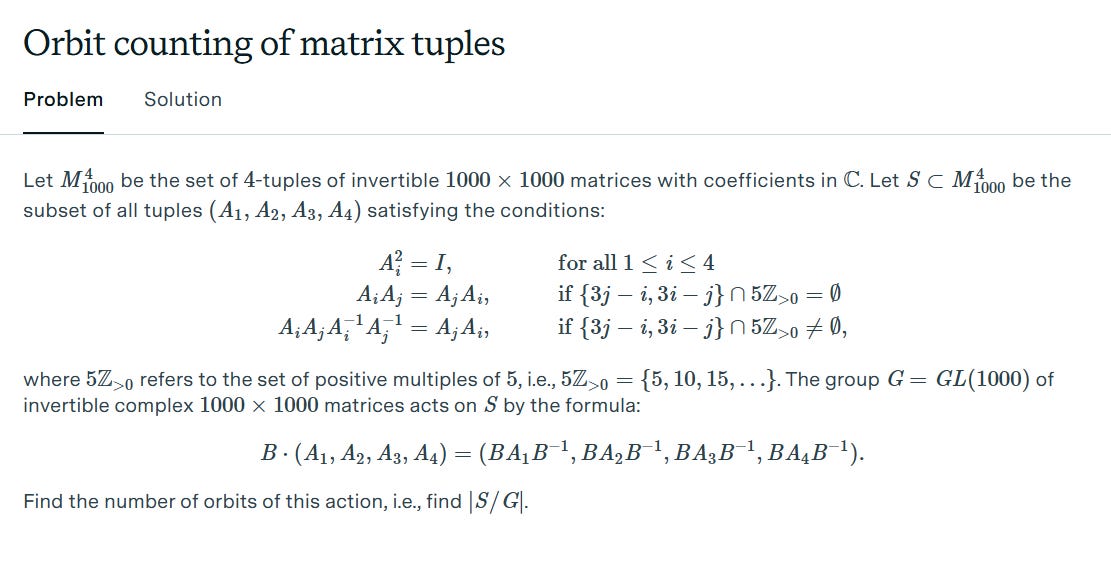

wrote back in January:One task that was meant to be devastatingly hard (Frontier Maths) has been cracked (25% achieved, up from 2%) by OpenAI’s new model O3. if you think that’s not too impressive, solve this problem from the easiest set in Frontier Maths or name three people you know who could:

If you think the risk is not real, I challenge you to nominate a concrete activity AI will need to be able to do before it can take over most white-collar jobs, that you are confident it will not be able to.

Most of this essay deals with critiquing Beha’s article. Since I don’t have the space in this essay to thoroughly explain why AI is a risk, I’ll just note that we’re creating a technology that’s smarter than us and that we don’t fully understand. I will write more about this in the future. I’ll also forward sceptical readers to this article:

The argumentation Beha provides for his claim (that humans have the capacity for genius and AI in principle does not) exemplifies the worst tendencies of anthropo-centrism and -exceptionalism: i.e., the idea that humans are supernaturally endowed with a special place in the universe and special capacities, which will protect us from all threats, including AI.

This kind of blindness cannot be left to fester: it underlies the optimistic view of AI that says it won’t fundamental change or challenge our world and that any new kind of technology is axiomatically good, both economically and existentially. It’s a kind of blissful ignorance rooted in the fear of facing up to great challenges. But for our own sake and our progeny’s, we must remain wary of AI and face up to its risks. But first let’s dissect Beha’s argument.

On Human Genius

The premise of Beha’s view is that we are radically underestimating human ability; in particular, or our capacity for “genius.” Theoretically, it’s this uniquely human capacity for genius that will protect us. Beha admits that modern science leaves no room for the concept of genius except as the superlative extension of intelligence (in which case it isn’t really a new concept at all but rather a fun word we can use to mean “really, really smart”). Beha writes:

On the matter of human psychology, the neo-Darwinist subdiscipline of cognitive science tells us that our brains are algorithms for the processing of information. Through brute trial and error, we have learned which algorithmic outputs will produce material rewards….[T]he idea that individual humans might be capable of acting in ways not determined by millenniums of genetic history [has been removed from the picture].

Later he writes:

From the vantage point of cognitive science…the classic notion of genius makes no sense. Clearly some people have more processing power than others, but the idea of some cognitive quality other than sheer intelligence is incoherent.

This is correct. Beha rightly notes that cognitive science tells us that humans are not capable of acting in ways not “determined by genetic history.”2 A more clear way of putting it is that we are limited to our hardware: cognition is a physical process that happens in the brain; all of the brain’s physical and functional limitations are thus limits on cognition.

Humans will always be restricted by cognitive biases, the physical size of our brain that caps our “computing power,” and the “bugs” in our genetic code that make us petty, bigoted, shortsighted, and selfish, et cetera. Of course, humans also have an incredible ability to be kind, creative, productive, and cooperating. But the extent to which we display those features is always well within the predicted limits of cognitive science. No human as of yet has been so incredible as to make any reasonable scientist or philosopher question their theories about the brain and posit some kind of supernatural “genius” instead.3

But it seems Beha rejects cognitive science, rebuking it for removing “subjective, qualitative experience, which inevitably retains a hint of the spiritual” from the picture.4 What is he going on about? Belief in cognitive science doesn’t preclude belief in subjective, qualitative experience (qualia). Very few cognitive scientists (probably none) would deny the existence of that.5 And subjective experience isn’t inherently spiritual. The idea that it is is a remnant of the mistaken ancient theory that anything we don’t fully understand must be divine (the God of the gaps). I’m not saying it’s impossible that there exists something divine about qualia; I’m just saying that we should default to the position that qualia aren’t spiritual. And even if we were certain that subjective experience requires “spirituality,” that wouldn’t necessarily entail the existence of genius. Beha isn’t really clear about the logical steps in his argument, so I’m just trying to address what I assume he meant.

Poor Argumentation

The rest of Beha’s essay is kind of a mix of narrative history of the concept of genius and motivated reasoning. He never quite makes it clear why he believes humans have a special capacity that AI doesn’t. He certainly doesn’t provide any kind of argument as to why cognitive science is wrong other than to vaguely suggest that it must be wrong because it precludes spirituality.

Beha goes on to mention plenty of interesting philosophers, including Socrates, Marx, Barthes, Bourdieu, Kant, and Jameson, in an effort to show that lots of people throughout history have believed in human genius. To give you a taste of how Beha “argues” for his position, read this excerpt from near the end of his essay:

Ironically, our single greatest fear about AI is that it will stop following the rules we have given it and take all its training in unpredictable directions. In other words, we are worried that a probabilistic language-prediction model will somehow show itself to be not just highly intelligent but also possessed of real genius.

Luckily, we have little reason to think that a computer program is capable of such a thing. On the other hand, we have ample reason to think that human beings are. Believing again in genius means believing in the possibility that something truly new might come along to change things for the better. It means trusting that the best explanation will not always be the most cynical one, that certain human achievements require — and reward — a level of attention incompatible with rushing to write the first reply. It means recognizing that great works of art exist to be encountered and experienced, not just recycled.

As someone who cares deeply about the risks and benefits that AI could bring to the world and who is fixated on finding the truth via rational argumentation, reading this is frustrating. Let’s take it line-by-line:

[O]ur single greatest fear about AI is that it will stop following the rules we have given it and take all its training in unpredictable directions.

Yeah, kinda. This makes me fear Beha is unfamiliar with the current state of AI safety and capabilities research. Really the case against AI is far more nuanced than “we fear a probabilistic language-prediction model will go off the rails and ignore its instructions.” Beha ought to look into the foundational concepts of goal-intelligence orthogonality and instrumental convergence, which (basically) argue that AIs could still do really bad, immoral things even if they’re super smart and even if their ultimate goals are neutral or even altruistic.

[W]e have little reason to think that a computer program is capable of such a thing.

Here he’s referring both to the fear that a computer program is capable of taking “its training in unpredictable directions” and the fear that it is not just highly intelligent but possesses genius. We actually have plenty of reason to think AI could go off the rails. Lots of smart people have written about this and Beha addresses none of their arguments.

Regarding genius, Beha makes no argument as to why it exists in humans or in AI, and I see no reason to posit it exists in either. All I know is that AIs are already way smarter than humans in many domains and have the power to create art, music, and poetry that no one can tell wasn’t made by a human. What even is this inscrutable, undetectable “genius” that humans have? If we can’t discern human-generated from AI-generated text and art, then how can human “genius” be real? Is it one of those great theories about the world and the universe that is impossible to empirically test and has no actual impact on anything?

On the other hand, we have ample reason to think that human beings are [capable not just of high intelligence but also of real genius.]

Again, we do not have ample reason to believe this. Throughout the essay Beha cites various figures who asserted that humans have some kind of supernatural intelligence without ever making an argument for it. For example, here’s what Beha says about Kant:

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant claimed all truly great art—the kind that could transform us rather than simply entertain us—was the product of genius. Whereas conventional artistic creation involved imitation and the following of existing procedures, geniuses made their own rules. They acted not by science but by inspiration, with all of the spiritual trappings that term implies.

This is not an argument! Why would this be true? There are tons of things that Kant believed that seem not at all plausible to me.

On Socrates, Beha writes:

Socrates claimed throughout his life to be visited by a spirit — “daimonion” in Greek, “genius” in Latin.

OK, but maybe Socrates was wrong about this, no?

Of “the Christian era,” Beha writes:

[T]he person touched by genius gave way to the mystic-saint who had achieved ecstatic moments of unity with God….Reality had deep truths that could not be arrived at by way of the intellect, and these truths could make themselves manifest in surprising ways.

Again, why is this true? There’s lots of stuff that people in Medieval Europe believed in that turned out to be wrong.

On modern thinkers, he writes:

Figures like Einstein, Gödel, von Neumann and Oppenheimer were thought to possess intuitive powers that seemed only tangentially related to their quantitative abilities.

Just because someone was thought to be a genius doesn’t make them one! I won’t bore you with more of this, but most of the meat of Beha’s essay is like this: a list of historical figures who thought humans possessed some kind of supernatural capacity that is inexplicable in scientific terms called “genius.”

Back to the conclusion of the essay. Beha writes:

Believing again in genius means believing in the possibility that something truly new might come along to change things for the better.

What does this mean? Is it meant to be an argument in favour of genius existing on the basis that we axiomatically ought to believe “in the possibility that something truly new might come along?” If so, does this axiomatic belief always entail genius? Why? And why should we posit it as axiomatically true? And if this whole thing is not an argument for genius but rather the implication of belief that humans have genius, then why does it logically follow? It’s just ridiculously vague.

[Believing in genius] means trusting that the best explanation will not always be the most cynical one, that certain human achievements require—and reward—a level of attention incompatible with rushing to write the first reply.

Honest to God, I have no clue what that means.

[Believing in genius] means recognizing that great works of art exist to be encountered and experienced, not just recycled.

Why would this vague normative belief about how we ought to interact with art be correlated with the existence of genius? And again, is this meant to be an argument in favour of genius existing because it’s true that we ought to “encounter and experience” art rather than recycle it? (If so, it’s missing a few logical leaps!) The normative claim about how we ought to appreciate art establishes nothing empirically about whether or not genius exists. It’s the equivalent of claim that “believing in leprechauns means that Saint Patrick’s Day is a day for rejoicing.” It’s a nothingburger.

Motivated Reasoning

Throughout the essay, Beha fails to separate what he wants to be true from what he thinks is actually true. Here are some examples:

“The combined influence of [cognitive science and Marx-inflected critical theory] has been enormous. As many commenters have noted, our culture has largely given up on originality.” (Beha doesn’t like these views because they deny the existence of genius.)

“[T]his cultural leveling [i.e. the denial of human genius] has…brought a persistent feeling of anti-humanist despair. What has been entirely lost in all of this is any hope that some combination of inspiration and human will could bring something truly new into the world, that certain works of individual insight and beauty might transcend the admittedly very real influences of political and economic contexts in which they are created.”

“[T]he alternative [to believing in genius] is a stultifying knowingness.”

So why am I picking on this guy so much?

First, I’m annoyed the The New York Times would publish this. But as I’ve previously written, the Times has published poorly argued essays in the past.

Second, I see motivated reasoning and other kinds of wacky irrational arguments all the time in public discourse, and they need to be vigourously confronted. Humanity faces many existential challenges—like the threat from AI, nuclear war, pandemics, and climate change—and we’re gonna need rational argumentation to figure out what policies to pursue and how to face up to these challenges.

Mainly, I’m concerned that Beha is encouraging people not to fear AI. By arguing that humans possess a special genius that AI will never have, he lowers our guard, ensuring us that everything will be OK because we can always outsmart the machines. It seems far from clear to me that we can.

I actually wrote this back in January but sat on it for some unexplicable reason. There are like 100 almost-complete blog drafts on my Substack dashboard.

I would add that we can’t act in ways contrary to the physical laws according to which particles in the universe behave, be they not just in our minds but also in our environment.

Granted, there’s much we don’t understand about the brain, and there are some good philosophical arguments for the divine, some of which hinge on the inexplicability of certain aspects of the mind such as psychophysical harmony (the parallelism between that which we subjectively experience and the physical world around us). But no reasonable philosopher or scientist would defer to the unparsimonious view that the smartest of us are endowed with a divine gift—genius—that transcends mundane human intelligence.

This is not a very scientific phrase! It’s totally unclear what “removing from the picture” means. If you’re trying to make scientific and philosophical claims about the capabilities of humans and machines and the future of mankind, use rigourously defined words and phrases.

Dan Dennett might deny it.