61% of Democrats think they’re cool; 54% of Republicans think they’re cool.

Polling on what Americans think of Luigi Mangione and others:

Excerpt from Henry Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi:

“Of course there is this to remember—the Greek only killed one man, and that in righteous anger, whereas the successful American business man is murdering thousands of innocent men, women, and children in his sleep every day of his life. Here nobody can have a clear conscience: we are all part of a vast interlocking murdering machine. There a murderer can look noble and saintly, even though he live like a dog.”

I guess we know where he’d stand on the Luigi issue.

Word of the day: thalweg

China Hawkflation is a thing:

Harvard PhD student Michael Cerny and Princeton’s Rory Truex have a working paper on how reputational concerns incentivize foreign policy professionals to become more hawkish on China. They did a survey of 495 people and conducted 55 semi-structured interviews, finding that “[r]oughly one fourth of survey respondents noted instances of professional pressure to voice a more hawkish point of view towards China, and many feared being perceived as naïve or compromised by their views on, ties to, and experiences in China. These pressures were particularly noteworthy for foreign policy … who are younger, non-white, or female.”

“Though direct censorship, self-censorship, and preference falsification do occur, more commonly our subjects revealed the tendency to engage in what we term discourse mirroring—instrumentally framing ideas and recommendations in the prevailing language of threat in order to be more persuasive. This has the effect of what one interview subject called “hawkflation,” with individuals appearing more hawkish and confrontational than they actually are, especially to those who do not know them well.”

This ups my credence in the existence of a foreign policy blob.

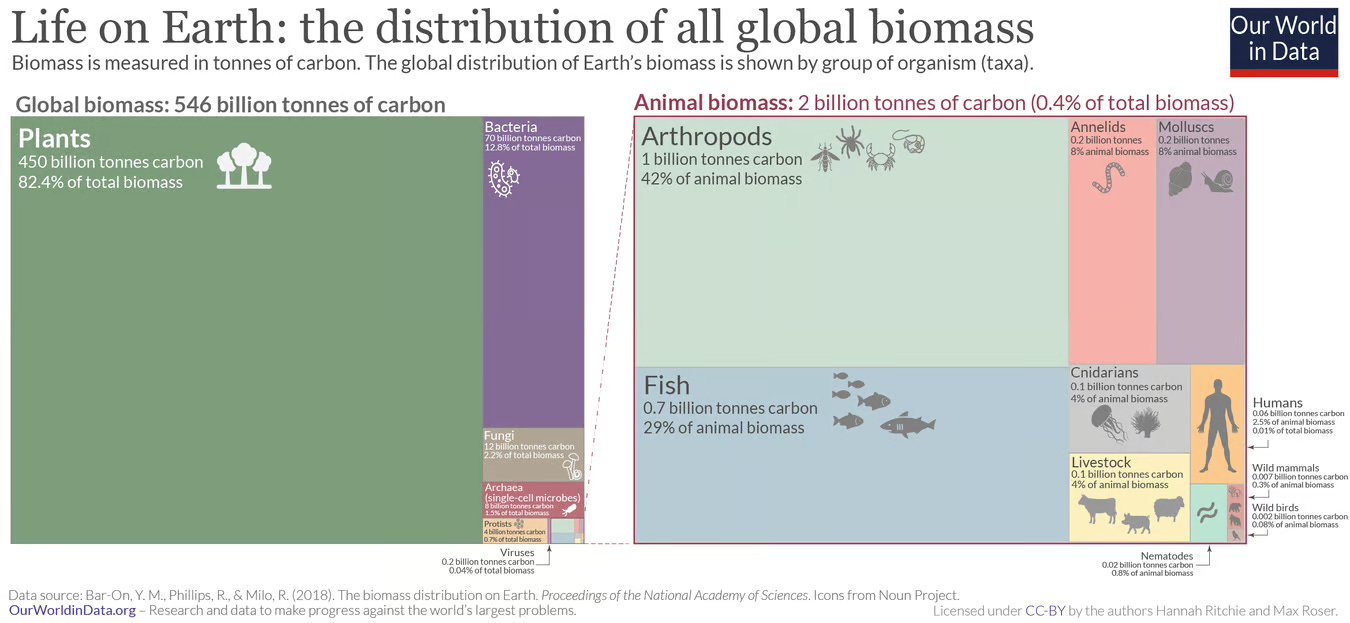

The biomass of all bacteria exceeds that of all humans by a factor of 1170

In honour of our new overlords, here’s James K. Galbraith writing on oligarchy:

In my 1989 book, I suggested a rough emerging hierarchy of nations: advanced technological (and I would now stress, financial) powers, intermediate manufacturing powers, and resource-based economies. The world has developed along these lines. In consequence, countries like ours (the US, UK, Canada) are now run by gangs of oligarchs, rooted in finance, technology, energy, aerospace, the military, big Pharma, insurance, real estate. Their struggles are mainly with each other. Labor as such has little-to-no leverage; it subsists on social minima, a strong currency, cheap energy, and (it must be said) the Schumpeterian gains from radical improvements in (mostly imported) consumer goods. For this reason, pressures for inflation are driven by resource costs, first and foremost, and after that by speculative competition between the various monopolists. As Josh Bivens has documented, the big recent gains are in profits. It’s an oligarch’s world, we only live here.

I saw this painting (Pinching the Frenulum) by Ilana Savdie at the Montreal Art Museum and liked it a lot.

I recently stumbled upon Jean Langlais, and I love his work:

Dating is people’s 34th most popular social activity, right after attending sporting events (32rd) and drinking (33rd). The 35th most popular social activity is going to the ballet/dance performances.

Cool excerpt from John Updike’s Rabbit, Run:

Fritz Kruppenbach: “There iss no up to a point! There is no reason or measure in what we must do . . . If Gott wants to end misery He’ll declare the Kingdom now. How big do you think your little friends look among the billions that God sees? In Bombay now they die in the streets every minute. You say role. I say you don’t know what your role is or you’d be home locked in prayer. There is your role: to make yourself an exemplar of faith. There is where comfort come from: faith, not what little finagling a body can do here and there, stirring the bucket. In running back and forth you run from the duty given you by God, to make your faith powerful, so when the call comes you can go out and tell them, ‘Yes, he is dead, but you will see him again in Heaven. Yes, you suffer, but you must love your pain, because it is Christ’s pain.’ When on Sunday morning then, when we go before their faces, we must walk up not worn out with misery but full of Christ, hot.”

There’s a U.S.-run detention camp in eastern Syria

The Gulf/2000 Project at Columbia makes awesome maps of the Middle East. Here’s a cool Map of Islamic states in 1350

Biafra declared independence again? They did it in Finland, though.

This Syrian rebel group has a really cool logo.

I had Claude translate a passage from philosopher and priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s Je m’explique. He touches on panpsychism, determinism, and free will:

Purely inert matter, totally raw matter, does not exist. But every element of the Universe contains at least an infinitesimal degree of some germs of interiority and spontaneity, that is to say, of consciousness. In very simple and extremely numerous corpuscles (which manifest themselves to us only through their statistical effects), this property remains imperceptible to us, as if it were not there. On the contrary, its importance grows with complexity, or, which amounts to the same thing, with the degree of “centration” of corpuscles on themselves. From an atomic complexity of the order of a million (virus), it begins to emerge in our experience. Higher up, through successive leaps (by a series of psychic “quanta”), it becomes evident. In humans, finally, following the critical point of “reflection,” it reaches the thinking form, and from then on it becomes dominant. Just as large numbers, in the infinitesimal, explain the determinism of physical laws, and just as spatial curvature, in the immense, accounts for gravitational forces; thus in the third infinite, complexity (and the centricity that it entails) gives rise to the phenomenon of freedom.

The original French:

La matière purement inerte, la matière totalement brute, n’existe pas. Mais tout élément de l’Univers contient à un degré au moins infinitésimal, quelques germes d’intériorité et de spontanéité, c'est-à-dire de conscience. Dans les corpuscules très simples et excessivement nombreux (qui ne se manifestent à nous que par leurs effets statistiques), cette propriété nous demeure imperceptible, comme si elle n’était pas. En revanche, son importance grandit avec la complexité, ou, ce qui revient au même, avec le degré de « centration » des corpuscules sur eux-mêmes. À partir d’une complexité atomique de l’ordre du million (virus), elle commence à émerger pour notre expérience. Plus haut, par saccades successives (par une série de « quanta » psychiques), elle se fait évidente. Dans l’homme enfin, à la suite du point critique de la “réflexion”, elle atteint la forme pensante, et dès lors elle devient dominante. De même que les grands nombres, dans l’Infime, expliquent le déterminisme des lois physiques, et de même que la courbure spatiale, dans l’immense, rend compte des forces de gravité ; ainsi dans le troisième infini, la complexité (et la « centréité » que celle-ci entraîne) donne issue au phénomène de liberté.

Philosopher Derek Parfit on the sublime:

Even if these questions could not have answers, they would still make sense, and they would still be worth considering. I am reminded here of the aesthetic category of the sublime, as applied to the highest mountains, raging oceans, the night sky, the interiors of some cathedrals, and other things that are superhuman, awesome, limitless. No question is more sublime than why there is a Universe: why there is anything rather than nothing.

Philosopher Amia Srinivasan on bestiality (zoophilia, actually).

Great Bertrand Russell quote:

The next stage in the development of a desirable form of sensitiveness is sympathy. There is a purely physical sympathy: a very young child will cry because a brother or sister is crying. This, I suppose, affords the basis for the further developments.

The two enlargements that are needed are: first, to feel sympathy even when the sufferer is not an object of special affection; secondly, to feel it when the suffering is merely known to be occurring, not sensibly present. The second of these enlargements depends mainly upon intelligence. It may only go so far as sympathy with suffering which is portrayed vividly and touchingly, as in a good novel; it may, on the other hand, go so far as to enable a man to be moved emotionally by statistics. This capacity for abstract sympathy is as rare as it is important.

I remember watching every new edition of Live from Emmet’s Place during the pandemic, and this was the coolest one.

This guy makes track maps of metro systems. Here’s central Paris:

Glenn writes one of my favourite Substacks. This essay on U.S. foreign policy failures is great: